Transmission: An Interview with Artist Charles Carroll

There’s a raw energy in the moment just after graduating, when nothing is fixed and everything matters. For queer artists especially, this threshold holds both uncertainty and urgency, a moment suspended between what has been and what could be. These conversations capture artists on the cusp, still carrying the intensity of making under pressure, and beginning to shape what kind of future they might insist into being.

As part of our ongoing conversations with queer graduating students from UCA (University for the Creative Arts) about their degree show work, we spoke with Charles Carroll about the role of language, storytelling, and identity in his practice. Beginning with poetry but expanding into installation and moving image, Charles’s work explores queer romance, miscommunication, and the ways we make meaning from lived experience. In this conversation, he reflects on his shift from painting to writing, the politics of asking questions, and the lyricism that connects books, films, and art making. What emerges is an artist attuned to narrative and feeling, creating work that holds space for intimacy, resistance, and connection.

***

Pup and Tiger: Can you tell us a little about the work you showed in the degree show?

Charles Carroll: My practice as it stands examines the human experience through a queer lens. Often autobiographical in nature, my work aims to use textual and visual elements to invent narratives that speak to the wider queer communities.

A main theme in my work that is explored is queer romance, my work as a writer and as a maker are both inspired by my interest in human connection, particularly when concerned with queerness. I am interested in the distortion of language, miscommunication, and more recently in my research, a close interest in how language and miscommunication contribute to issues such as colonial histories, racism, homophobia, and social justice.

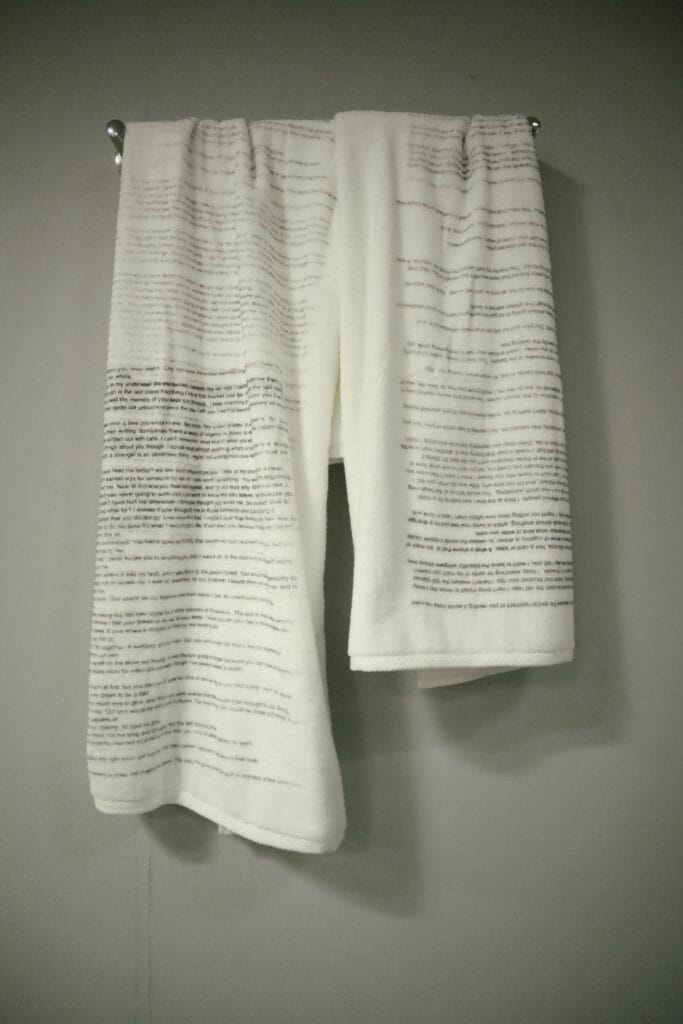

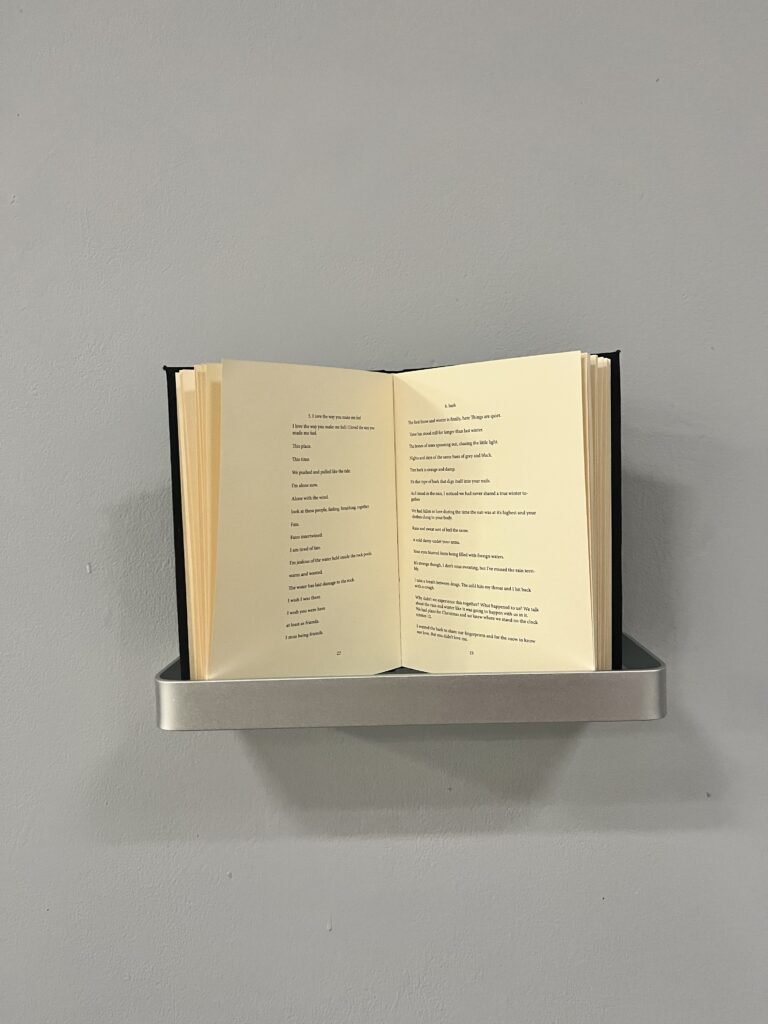

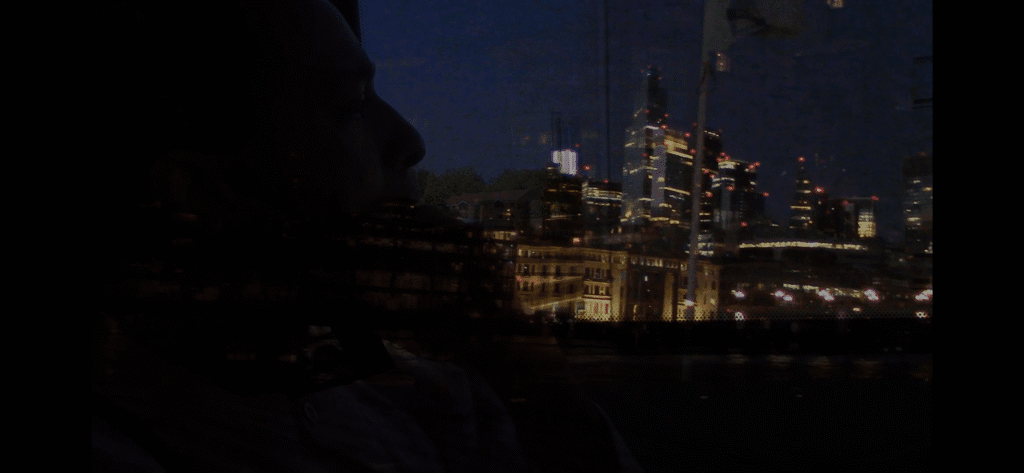

In terms of material, I was interested in showing how expansive making text work could be. I did this through script writing, printing, and a more traditional book format. For the piece “Two Lovers” (towel rack) the idea was stripping the object of its intended purpose and creating an object of viewing and reading. I found film works well as a conduit to express my poetry visually. The book was to call back to more tangible ways of reading, something familiar to people who aren’t part of the “art world”.

PT: What drew you to make this kind of work?

CC: I’m drawn to my way of practicing because it feels most authentic to my life experience. I’m often captured by song lyrics or passages in books; these really stick with me. These moments are when I am most inspired to make work and to write.

As a queer person, focusing on queer narratives feels both right and responsible. I believe as a queer person who has been born after the fight for our rights to exist, it is my mission and responsibility to continue the fight and maintain the community.

PT: You mentioned in your video piece Where the trees touch that it is a dangerous time to question, what does that mean to you?

CC: My work aims not to be political, but as a queer artist this means the fact that I make art at all is a political statement. In saying that, to question authority and government is a right for a democratic society and I see that those rights are being stripped away. Not just locally, but globally we are moving backwards.

Also, speaking on the dangers of asking questions speaks to the epidemic of existentialism in my generation. Too often are young people faced with trials that they don’t have tools to tackle and questions they don’t know the answer to.

PT: Has your work changed a lot during your time at university? How do you think it’s grown or shifted?

CC: I started off as a painter, mostly self-portraits and religious iconography. I went a traditional route through art, learning the discipline of painting, and I followed these ideas throughout my first year until I hit a wall. I was challenged to paint less and began exploring queer culture openly. I would go back to painting sometimes but always found my work most successful in times where my writing was the focal point.

I also found that I loved films and books so much that I had a need to make them and to be a part of that world. I began to become obsessed with the lyricism in these mediums and the celebration of narrative. This was an epiphany for me.

PT: What’s something you’re feeling curious or excited about now, in your art or just in general?

CC: I’ve become increasingly excited and interested in understanding of colonial histories, the effects this has on art, and how as a white person I can sensitively have dialogues on these issues and give voice to artists from native or indigenous communities.

I am also excited about the opportunities writing can give me. Being from a fine art background and moving into writing can seem strange to some but the connections between visual art and writing is what makes “capital A” Art.

PT: Are there any artists, writers, films, or music that have been feeding into your practice lately?

CC: I have been reading a lot of queer and black writers such as Jason Haaf or Oluwaseun Olayiwola, both of these writers find ways to speak on love, grief, and everything in-between in beautiful lyrical ways that really inspire me.

I listen to way too much music, but a favourite artist of mine is Ethel Cain, whose music I listen to when I write. I find it helps me move through the writing whilst maintaining rhythm, but also I can visualise my films in my head when I am fed with her music, there is lots of space to think when she sings. It’s very mediative.

PT: What’s something you wish people knew or understood better about your work?

CC: I want people to relate to my work and understand that I write from experience. I write to share these experiences and for them to know that I’ve processed these times in my life and it’s safe to explore those moments with me.

I think I’m still figuring out how to be entirely vulnerable with my work, I still find myself editing out parts to better fit the pallet of a wider audience, but I believe that this is a learned behaviour that I will soon grow out of.

PT: Finally, where can people follow your work or see more of what you’re doing?

CC: I post regular on my Instagram Charles_Carroll_art

***

Transmissions is an ongoing series from Pup and Tiger, spotlighting voices across queer art and cultural practice. We publish interviews, essays, and experimental texts that offer space for artists to speak in their own words and on their own terms.

Pup and Tiger is a queer-led art space and project platform based in Canterbury, UK. We champion emerging practices, experimental forms, and collective cultural work rooted in care, resistance, and reimagining.

Are you a recent graduate artist and would like to be interviewed for this Transmissions series? Reach out to us at [email protected].

About the Artist

Jared Pappas-Kelley is an artist, writer, and co-founder of Pup and Tiger. His work has appeared in Art Monthly, The Guardian, 3:AM Magazine, Cabinet, and The Rumpus. He is the author of Solvent Form: Art and Destruction, To Build a House That Never Ceased, and Stalking America. Pappas-Kelley has curated exhibitions internationally and has led several independent art spaces and collaborative initiatives, including Critical Line, Tollbooth, and Don’t Bite the Pavement.