Transmission: An Interview with Artist Kat Hicks

There’s a raw energy in the moment just after graduating, when nothing is fixed and everything matters. For queer artists especially, this threshold holds both uncertainty and urgency, a moment suspended between what has been and what could be. These conversations capture artists on the cusp, still carrying the intensity of making under pressure, and beginning to shape what kind of future they might insist into being.

As part of our ongoing conversations with queer graduating students from UCA (University for the Creative Arts) about their degree show work, we spoke with Kat Hicks, a genderfluid artist working with stained glass. Their self-portrait is based not on visual likeness, but on a recorded moment of cardiac crisis, reimagining what a queer body in flux can look like. In this interview, Kat reflects on chronic illness, community, and the shift from grief to stubborn hope as the foundation for their practice. What emerges is a striking portrait of a young artist claiming space, light, and complexity in equal measure.

***

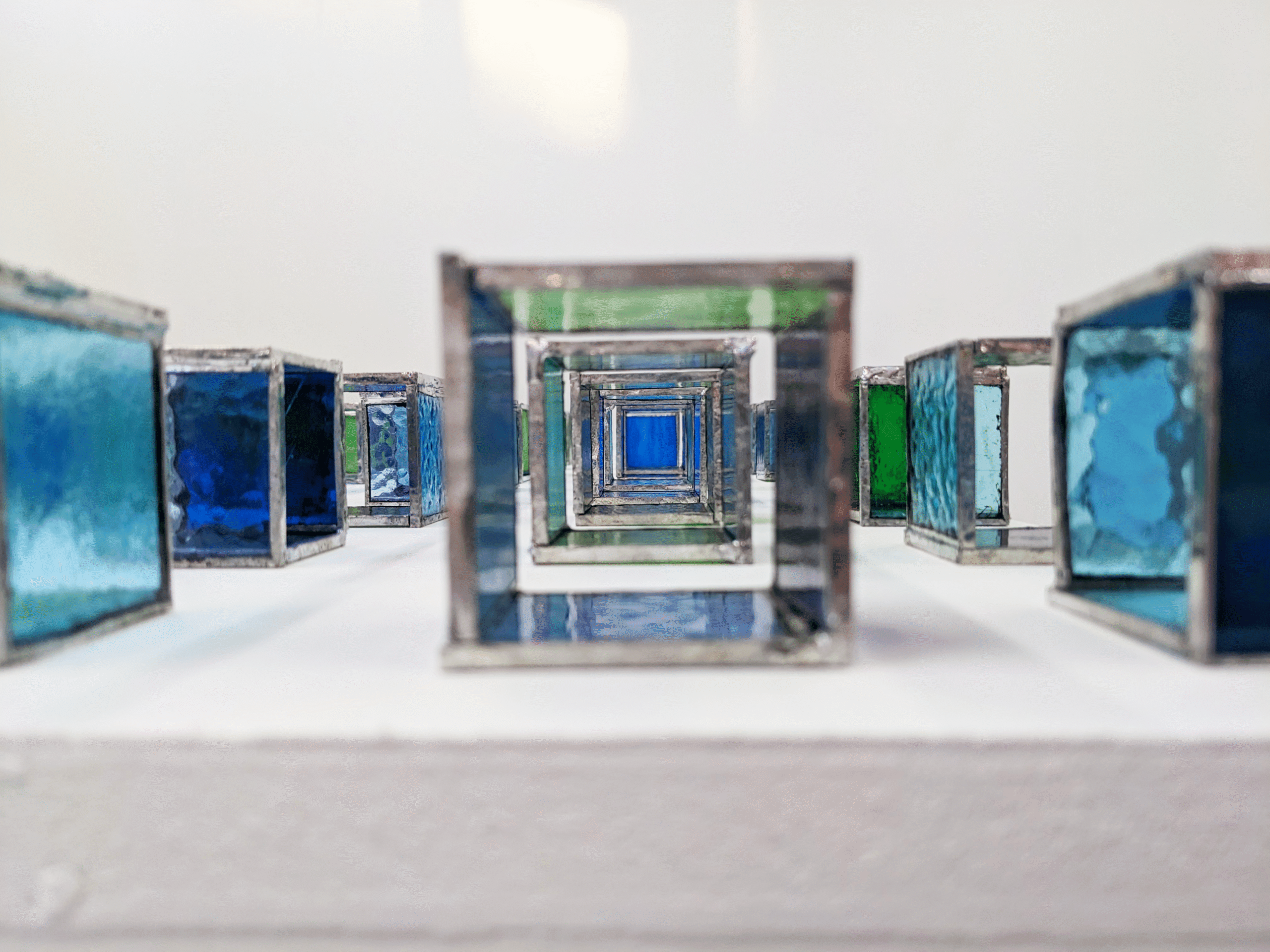

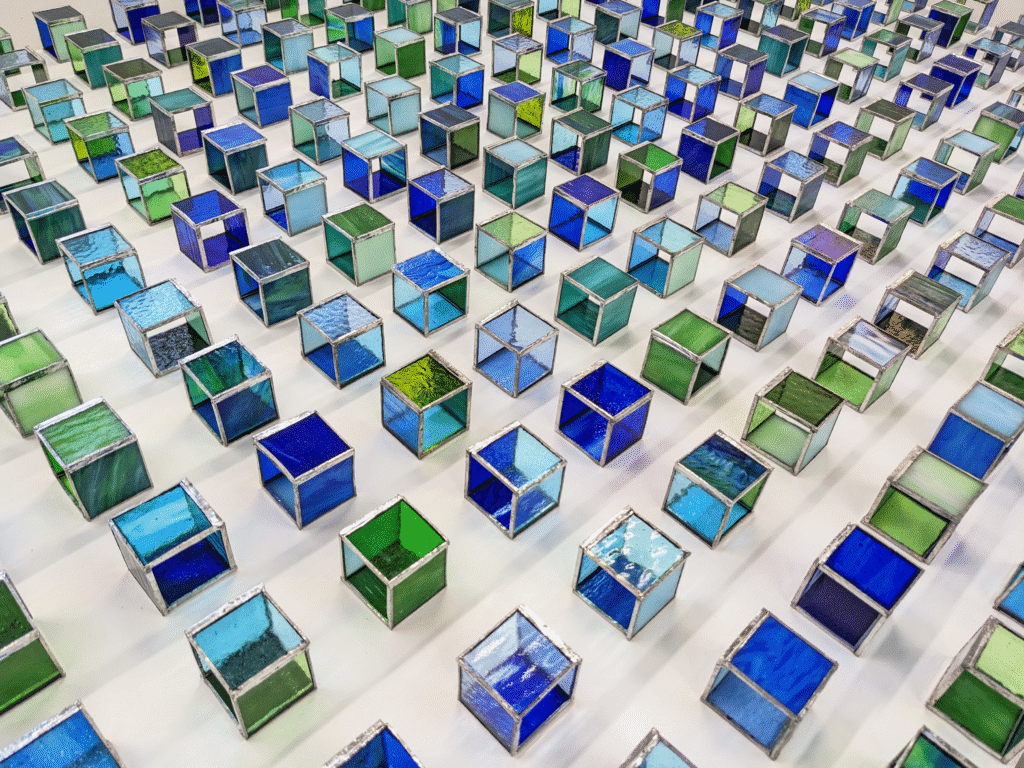

Pup and Tiger: Can you tell us a little about the work you showed in the degree show? You mentioned it as a self-portrait representing the heartbeats in a single minute?

Kat Hicks: I am very aware of the fact that it isn’t what someone would expect when you hear the term ‘self-portrait’, people hear it and think of a face, likely smiling, maybe surrounded by some personal effects or symbolic imagery. I call it a Self Portrait as it is a snapshot of a single minute of my life back in November, I was on a video call with a (slightly tipsy) friend in Australia while I was putting groceries away, and suddenly my heart started hammering for no reason. My disabilities have me largely housebound, only leaving to go to university or the hospital, if I were to make a traditional ‘self-portrait’ I would treat the public to eye bags that out my insomnia just as well as my rainbow shoelaces out my sexuality. By making this piece I pared back from the visible reality of my failing body, and present what was an invisible event that occurred while I was simply living my life- chatting and laughing with friends.

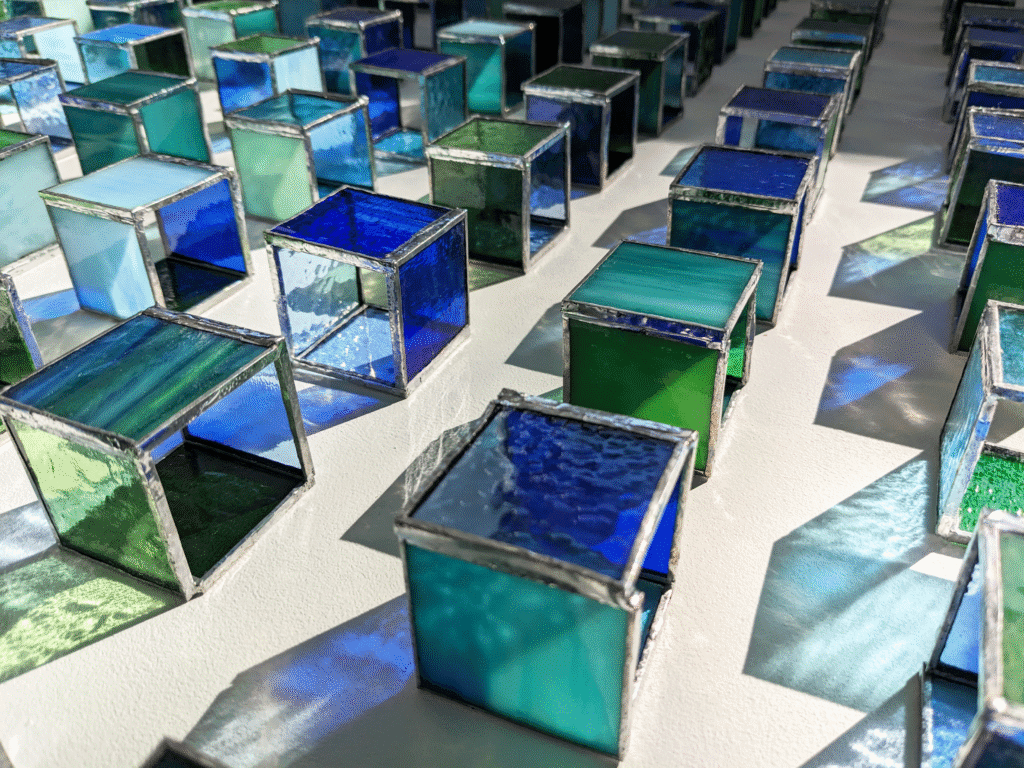

The choice of glass as a material is a return to my practice before I came to UCA. In the past I have worked with glass scraps to save my old glass tutor from having to throw anything away. For this project I used only blues and greens, symbolic colours to my practice and (outside of a few exceptions) the only colours I use nowadays, and made my way through nearly all the blue and green glass I owned – using both full sheets and offcuts. Coming from a photography background before turning to Fine Art, light is one of the most important and thought-out aspects of my practice and stained glass is a wonderful medium to work with. While I made Self Portrait (09/11/2024), the light that shines on it and changes over the course of the day is what brings it to life.

Taking three months to make (including an unfortunate amount of very late nights trying to get each stage done to meet deadlines) this has been by far my most ambitious project. The repetitive aspects of each step needing to be undertaken just over a thousand times proved to be therapeutic, I had a lot of time while marking out the glass, or foiling it, or any of the other processes, to simply think about my health – the limitations it imposes on me, and also to feel endless gratitude towards my darling fiancée who supports me through the harder times and brings enough joy to my life that even on my worst days she can have me howling with laughter.

PT: What drew you to make this kind of work?

KH: For the first half of this academic year, I had been searching for a way to move my practice forwards without including my health, as I had been warned away from it by one of my tutors. I’ve had heart issues as long as I can remember so I didn’t pay much mind to my heart racing in November on the call with my friend, but it was caught by my heart implant. When I was contacted by my cardiologist, I had to face the reality that it was far more serious than I had first assumed. To be told that if I went through similar symptoms, it warranted a natter to the lovely people manning 999 was a shock, and my cardiologist was kind enough to tell me the rate caught by my implant – 221 bpm.

With my health continuing to be such a cornerstone in my life, and having read Sick Woman Theory by Johanna Hedva, I realised that I needed to make work about my health – not just for myself, but to push past the social construct of health issues as something that must be curated and carefully managed to be as unseen as possible to pose as an acceptable part of society. I spend a significant amount of energy appearing as ‘functional’ as possible while I am out of the house, often to my own detriment. Self Portrait (09/11/2024) is a public reminder of invisible disabilities, a conversation that I am unable to have with every passerby, as well as a reminder to myself to give my body the time and gentleness it needs when flares occur. On the opening night of the Grad Show, the most gratifying part was talking with people about health, be it their own or that of family or friends. Opening up and starting conversations about health gives space for us to connect with each other, and recognise that we are all far less alone in our issues than we might think.

That interconnection, the community that these conversations bring, is exactly what I made my work for.

PT: Has your work changed a lot during your time at university? How do you think it’s grown or shifted?

KH: Before the pandemic I was largely focused on nature photography, and when my world shrank down to the size of my home in the spring of 2020, I began taking photographs of the sky from my bedroom window since I was feeling rather trapped. The blue of the sky made its way into ink pieces of the view from the window, then lino prints marking the days I and other immunocompromised people had been stuck inside, then fibre works that viewers were invited to pull apart, and has eventually made its way to where I am now.

I used to say that the underlying bedrock of my work was grief, the knowledge of loss that settles on your shoulders when you lose someone or learn that you won’t live as long as your peers. While it is still there (and I can’t say that I want it to fully leave) I would now describe the base on which my work is built is stubborn hope and honesty. If I have a limited amount of time to make my mark on this world, why shouldn’t I tell people about the truth of my lived experience? Why shouldn’t I bring up the fact that I’m with a woman the moment that people make assumptions about the ring on my finger? Why shouldn’t I make work that makes people confront the reality of young people being disabled?

I think that is the biggest change that has occurred since I started at UCA back in 2019, not making what I think would be ‘good art’ or attempting to use it to simply process my own troubles, but making something with the impetus of personal meaning that can reach out and connect with others.

PT: What’s something you’re feeling curious or excited about now, in your art or just in general?

KH: In October I am planning on continuing my studies with a shift from Fine Art into Art History and Visual Cultures, learning about the rich language and meaning that art holds across the world and in its various mediums is a lifelong task. Stained glass as a medium ranging from traditional sacred art to more domestic settings is something that has fascinated me for most of my life, and (health permitting) in about a decade I hope to be either firmly on my way to being Dr Hicks or will have managed to get my doctorate in some obscure rabbit hole topic that all of my friends will be very tired of. Outside of academia I am delighted that I will have more free time (at least for the next few months) now that the intense commitment of the final unit is over, and can spend more time my friends and fiancée.

PT: Are there any artists, writers, films, or music that have been feeding into your practice lately?

KH: Throughout this year I’ve been inspired by the work of Anya Gallaccio, her exhibition preserve at the Turner Contemporary was a joy to visit over the months that it ran, and her book provided a wealth of information and inspiration from her practice over the years. Her work touches on many topics and through succinct design choices presents them to her viewers in an accessible and thought-provoking way.

Grace Ayson is a local Ramsgate artist and conservator working in stained glass who I’ve been following for the past few years, and her lush and vibrant work has certainly had an influence on my practice. I would recommend that anyone visiting Canterbury cathedral checks out her works in the cloisters, her style is truly unique and utilises the qualities of glass and painting with mastery.

Having participated in a workshop run by her back in 2021, Max Chester and her bread dough works engaging with the ageing body and menopause have been feeding into my practice for some time now. Her works were an important step in understanding how aspects of the body can be presented in abstract ways, and the recent exhibition SHIFT was as powerful as it was beautiful – with its transformation from mobile and tacky bread dough hitting metal plating below with sonorous beats, to twisted shapes hanging from its metal grating.

PT: What’s something you wish people knew or understood better about your work?

KH: That I don’t just make work to look nice; I had another work described as ‘playful’ by one of my tutors and wasn’t given space to explain that it was made as an acknowledgement of my limited life expectancy due to my health issues. I know that the vast majority of people will simply glance at my work, without reading about it and its meanings, but I hope that those who do will be able to take the time to fully consider the works and why I have made them.

PT: Finally, where can people follow your work or see more of what you’re doing?

Instagram: @kat.hicks.99 (now I am done with my degree I will have more time to hopefully post things there!)

***

Transmissions is an ongoing series from Pup and Tiger, spotlighting voices across queer art and cultural practice. We publish interviews, essays, and experimental texts that offer space for artists to speak in their own words and on their own terms.

Pup and Tiger is a queer-led art space and project platform based in Canterbury, UK. We champion emerging practices, experimental forms, and collective cultural work rooted in care, resistance, and reimagining.

About the Artist

Jared Pappas-Kelley is an artist, writer, and co-founder of Pup and Tiger. His work has appeared in Art Monthly, The Guardian, 3:AM Magazine, Cabinet, and The Rumpus. He is the author of Solvent Form: Art and Destruction, To Build a House That Never Ceased, and Stalking America. Pappas-Kelley has curated exhibitions internationally and has led several independent art spaces and collaborative initiatives, including Critical Line, Tollbooth, and Don’t Bite the Pavement.